BOFIT Forecast for China 2025–2027

1/2025, published 28 April 2025

China’s economy continues to slow. The outlook for domestic demand remains depressed due to a lack of consumer confidence and prolonged problems in the real estate sector. China’s external prospects have also worsened. Output growth has outpaced domestic demand growth in recent years, with excess production going to exports. The trade war between the United States and China has increased uncertainty and weakened export demand. China’s other trading partners are also experiencing slowing demand growth, and many have become wary of their heavy dependence on Chinese imports further adding to trade tensions. This situation forces the Chinese government to take on increasing amounts of new debt to support the economy. Although we expect higher official growth figures, our forecast suggest China’s actual economic growth will remain below 4 % p.a. throughout the forecast period. Both upside and downside risks need be considered. Although a larger-than-expected government stimulus programme would boost growth, it would also exacerbate imbalances in the economy and financial market risks. External risks and uncertainty will remain high.

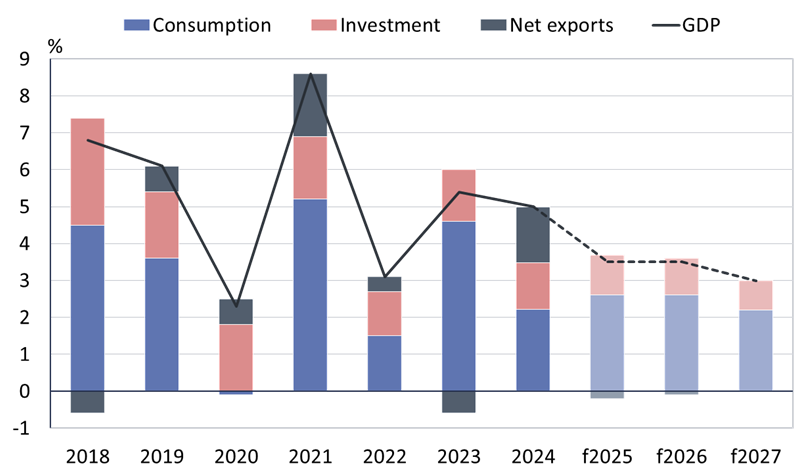

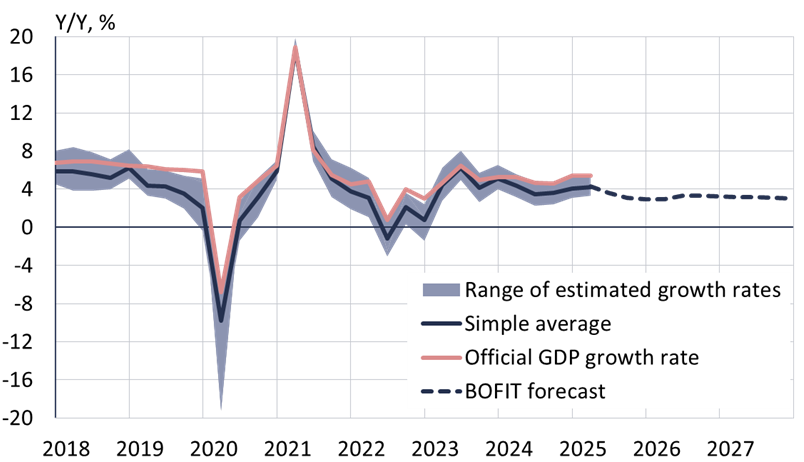

China National Bureau of Statistics (NBS) figures show the country’s gross domestic product grew last year at the official target rate of 5 %. Robust exports supported growth, with net exports accounting for 1.5 percentage points of GDP growth (Figure 1). Fixed investment growth also continued despite contracting real estate investment. Growth in domestic consumption, however, stayed relatively modest. BOFIT’s alternative calculation (Figure 2) suggests that GDP growth was about one percentage point lower than the official figure. Growth was relatively brisk also in the first quarter of this year, still supported by strong net exports. GDP grew officially 5.4 % y-o-y. BOFIT alternative estimate shows a growth rate somewhat above 4 %.

As in our previous forecasts, we expect structural factors to drive China’s economic growth slowdown. At the National People’s Congress in March, China again set a GDP growth target of “about 5 %” for 2025. Given the heavy lifting involved, it is highly unlikely that China reaches this year’s target. We expect China’s economic growth to remain around 3½ percent this year and next year, and then slow to around 3 percent in 2027, the final year of our forecast. As growth slows, disparities among branches and provinces should widen. Many branches could continue to experience robust growth. The political need to hit growth targets, combined with statistical deficiencies, make it challenging to assess China’s true economic performance.

Domestic demand determines economic outlook

Chinese consumer confidence has yet to recover to pre-pandemic levels. For example, over 60 % of respondents to a central bank survey at the end of last year said they preferred to build up savings, while just 25 % intended to increase consumption. Despite a government rebate programme to support sales of select home appliances, electronic devices and cars, real growth in retail sales last year barely exceeded 3 %. Chinese household savings are increasing rapidly and new borrowing falling despite attractive interest rates. As most Chinese household wealth is tied up in housing, falling apartment prices reduce household wealth. The NBS reports that apartment prices on secondary markets in March were down by nearly 20 % from their 2021 peak. Many regions have seen even steeper price drops. Weakening employment prospects further increase uncertainty. There have been long delays in public sector wage payments in many regions due to the growing financial struggles of local governments. There are also reports of private sector companies cancelling or reducing bonuses and non-wage benefits.

Both higher incomes and more robust private consumer demand are important in supporting economic growth. Private consumption accounts for a remarkably small share of economic activity (less than 40 %), while the savings rate is unusually high (44 %) for multiple reasons, including the country’s poor social safety net. While supporting domestic consumption was a top theme at this spring’s National People’s Congress, the measures announced to date have been quite modest. They are unlikely to increase household disposable incomes or reduce the savings rate to any appreciable extent. Most of the concrete measures proposed involve development of new products or services intended to boost consumer demand. Government consumption subsidies will be increased this year to 300 billion yuan, the equivalent to 0.2 % of GDP or 0.6 % of the value of retail goods sales. The increase will support the sales of the eligible items only temporarily. To sustain growth, the programme would have to be expanded every year.

We expect economic policy easing and targeted subsidy measures to stimulate private and public consumption during the forecast period. While reforms geared to improving employment and social security, as well as facilitating China’s transition to consumption-driven growth are important in raising the country’s long-term growth potential and sustainability, such reforms, unfortunately, are likely to be few and far between. Although the increase in the retirement age got underway this year, the fact that it will be incrementally implemented over 15 years means that it will only have a minor impact on growth during the forecast period.

The contractions in the real estate market and investment continue into their fourth year. Support measures have been increased and directed to the purchase of unsold apartments and land use rights with public assets, as well as easing apartment buying restrictions and lowering mortgage rates. These actions, however, have done little to ease the financial distress of real estate developers or staunch the bleeding in the sector. Support for real estate developers also consumes large amounts of public resources and ties up banking sector capital. In any case, the real estate sector now plays a diminished role as an engine of economic growth. Before the real estate sector crisis hit in 2021, the sector and related activity was estimated to account for 27 % of China’s total economic activity. That share is currently around 15 %. Housing construction and housing sales have contracted sharply and can be expected to bottom out during the forecast period, thereby reducing risk. The shift, however, is not expected to provide a significant boost to economic growth.

Fixed investment in recent years has been channelled away from building construction to manufacturing and infrastructure projects such as power transmission grids and renewable energy. Government support has been re-directed, for example, to investment in advanced technologies. The creation of new production capacity in several sectors continues to outstrip demand growth, meaning capacity utilisation rates have declined – a situation that has led to falling prices. Producer prices have been falling for nearly three years, a situation reflected in Chinese export prices. Industrial output grew by 6 % last year and remained strong in first quarter of this year. Escalation of the trade war will largely hit industries that rely on exports such as electronic devices and components. Companies will need to adjust their production chains and make investment decisions amidst significant uncertainty. In recent years, China has vigorously sought to increase domestic demand and self-sufficiency, especially in advanced technologies. This trend could receive further impetus if the trade war persists.

Escalating trade tensions restrain growth and increase export sector uncertainty

External demand has supported Chinese economic growth in recent years. WTO figures show that China’s export volumes are now up 39 % from pre-pandemic 2019. The volume of imports has increased a mere 6 % in the same period. We expect growth in export volumes in the forecast period to remain clearly lower than in recent years. Import growth should also remain weak due to slowing domestic growth and weaker demand for imported inputs for export manufacturing. We expect China’s current account to stay in surplus, but those surpluses should be smaller than in recent years. This will make the contribution of net exports to economic growth negative this year, and these effects should last well into next year.

The unprecedented tariffs imposed by the US on Chinese goods imports and the uncertainty from constantly shifting tariff policies have created and export demand shock, even if deterioration in bilateral trade relations was anticipated well before president Trump assumed office. At the time of this forecast, the US had increased the tariffs on Chinese goods imports by 145 percentage points from their January 2025 level. Taking into account the tariff exceptions on some products, along with the tariffs that have remained in place from the first Trump administration, the average import tariff for Chinese goods is estimated to exceed 120 %. China has responded with 125 % additional tariffs on all US goods, raising the average tariff rate already well above 140 %. Tariffs imposed during Trump’s first term were much more modest (below 20 % on average), and exporters were able to circumvent them by offshoring the final stages of production to third countries. In addition, the weakening of the yuan against the dollar eroded some of the effect from tariffs. The current situation is quite different. The US is threatening high tariffs on other countries, making the strategy of conducting trade with the US via third countries, such as Mexico and Vietnam, much more costly. Moreover, US tariffs policies and increased uncertainty slow growth of the global economy and hurt import demand. Even if China and the US manage to negotiate reductions in bilateral tariff levels, the situation will remain highly unpredictable and dim export prospects.

While China has increased its global market share, the importance of foreign trade for China’s economy has decreased. China accounts for 14 % of global goods exports and a fifth of all manufacturing exports. Share of foreign consumption in Chinese production has fallen over the past decade, but nearly 15 % of the value added produced in China is still consumed abroad. In 2020, the US consumed about 3 % of value-added produced in China, while the EU’s share exceeded 2 %. Export sector is also important for Chinese employment. The sector still employs over 100 million Chinese (about 15 % of the labour force).

About 15 % of Chinese goods exports have gone to the US in recent years, and roughly the same share to the EU. Redirecting US exports to other markets could be challenging, however. China’s trade relations have worsened with a growing group of countries concerned about the flood of cheap Chinese imports. For example, the EU, which is seeking to reduce its strategic dependence on China, last year imposed import tariffs on electric vehicles produced in China due to unfair subsidisation by the Chinese government. On the other hand, the shock from US tariffs to the global trade could cause other countries to strengthen their trade relations with each other. Potential positive outcomes from the current chaos could emerge if the Chinese authorities commit to levelling the playing field for foreign companies and improving the operating environment in China.

More economic stimulus looks inevitable

The escalation of the trade war means that the loosening of fiscal policy will likely well exceed the budget plan approved by the party in March, when the budget deficit was assumed to rise from 4.9 % of GDP in 2024 to 5.5 % this year in internationally comparable figures. A significant share of China’s public sector activity occurs off budget. Accounting for this activity, China’s total public sector deficit was in March expected to climb above 14 % of GDP this year (13 % in 2024). We expect the deficit to be even larger as more spending is needed to support growth, and future deficit reduction will be challenging. Public debt grows rapidly. The IMF estimates that China’s broadly defined (augmented) public-sector debt corresponded to 124 % of GDP at the end of 2024. The share is expected to exceed 140 % by the end of 2027.

Public imbalances are worsening. The growth in revenues is nowhere near enough to cover new expenditures. China has reinstated its pre-pandemic economic policy of setting overly ambitious GDP growth targets. To even approach the target figure, the government must invoke highly accommodative economic policies. Public sector reforms and increasing local tax revenues has been much discussed in recent years. Higher local revenue would be needed to reduce imbalances. Keeping the growth target as the main policy priority year in and year out, however, leaves little room for implementation of needed reforms or policy rebalancing.

The impacts of fiscal easing on economic growth are unclear. Most of the new easing measures in the current budget are directed at improving the public sector and banking sector stability, i.e. measures than have no immediate impact on the real economy. For example, local government debt will be increased by the issuance of more special bonds. The lion’s share of the money raised from the bond issues will go to paying off the debts of local government financing vehicles (LGFVs). Moving debt directly onto balance sheets reduces risk and improves the transparency of local government finances. Local governments, which have the biggest responsibility for implementing economic stimulus programmes, have had to resort to off-budget borrowing to fund stimulus measures. The IMF estimates that the LGFV debts of local governments have annually grown by about 2 percentage points of GDP in recent years.

Some of the new central government debt will be directed to recapitalising big state-owned banks, with a smaller portion going e.g. to covering the costs of the consumer trade-in programme for purchases of durable goods. Improving the financial condition of banks is important as risks in the sector have grown. The challenge is targeting stimulus measures to produce timely economic growth without creating new imbalances. The tried-and-true practice of relying on increasing infrastructure investment has reached a point of diminishing returns and can no longer be relied upon to boost growth as earlier.

Accommodative monetary policies aimed at supporting the economy have been surprisingly limited in recent years. The People’s Bank of China has lowered its main policy rates by just 0.75 percentage point since spring 2020, even if there is plenty of room for monetary easing with inflation near zero (–0.1 % in March). The increased outflow of capital and fears of a sudden drop in the exchange rate, however, limit the easing of monetary policy. The PBoC in recent years has limited yuan depreciation against the dollar by keeping its daily fixing rate, the midpoint around which the market exchange rate can fluctuate within a ±2 % band, very stable. The central bank is unlikely to permit any substantial drop in the yuan-dollar rate in order to support exports. With the weakening of the dollar this year, the yuan has depreciated against many other currencies, which, in turn, supports exports outside the US.

Uncertainty overshadows this entire forecast

This forecast comes with significant upside and downside risks. Weak fiscal conditions in many regions, combined with increased off-budget borrowing, have boosted financial market risk. The reduced profitability of the banking sector is worrying as the financial sector is more sensitive than earlier to disturbances and the public sector buffers to deal with problems as they arise have become thinner. This heightens the risk of contagion, whereby financial sector distress spreads to the real economy. It remains difficult to evaluate the true situation of the economy as free discussion on economic issues is restricted and some of China’s statistical reporting serves political purposes. This situation is also problematic for China’s decision-makers themselves.

Economic growth in the forecast period can exceed the forecast if the government increases its stimulus efforts more than expected. Such moves, while perhaps politically expedient, worsen economic imbalances and reduce growth potential in coming years. On the other hand, reforms such as raising the retirement age, increasing domestic consumption, reducing the hidden off-budget debt of local governments and diminishing risks to the banking sector are welcome. It is encouraging that the government has taken at least preliminary steps towards their implementation. More focused realisation of structural reforms would increase China’s growth potential over the longer term. Growth can also fall below the forecast if economic stimulus measures are smaller than expected or if they fail to support the real economy.

Among rising external risks, trade policy uncertainty is particularly high. Destabilisation of international trade system could have a larger-than-expected negative effect on the global economy. Upside risks to this forecast include the possibility that the US and China manage to calm the current situation. The likelihood of downside risk is boosted if the pursuing of geopolitical goals overrides economic objectives. China’s broader support for Russia’s war of aggression in Ukraine, advancing publicly declared intentions about annexing Taiwan or more aggressive behaviour in its neighbouring regions would have major negative repercussions for its domestic economy as well.

» Download the presentation from the webinar (PDF)

Figure 1. China’s GDP growth, factors contributing to growth and BOFIT forecast for 2025–2027

Sources: China National Bureau of Statistics and BOFIT.

Figure 2. BOFIT’s alternative GDP estimate and BOFIT forecast for 2025–2027

Sources: China National Bureau of Statistics and BOFIT.