BOFIT Weekly Review 17/2024

US Congress passes long-awaited military assistance package for Ukraine

The US Congress passed a $61 billion support package for Ukraine and President Joe Biden signed the legislation into law on Wednesday (Apr. 24). The hefty aid package consists mostly of military assistance to ease Ukraine’s acute shortage of military material. The package dedicates roughly $13 billion for restocking US weapons inventories, $14 billion to Ukraine for purchases of American defence material, $14 billion for purchase of high-tech weapons systems and $11 billion for enhancing regional security around Ukraine. About $8 billion of the aid package is direct budget support that Ukraine can use to pay pensions, social security and other mandatory government expenditures.

At the same event, the president also signed the Rebuilding Economic Prosperity and Opportunity for Ukrainians (REPO) Act with provisions that grant the president power to confiscate Russian sovereign assets within US jurisdiction and use those assets to support Ukraine. In the EU, the discussion on the use of Russian assets to compensate Ukraine has largely focused on seizing income generated by Russia’s frozen assets in Europe. It is estimated that G-7 countries collectively hold about $300 billion of blocked assets of the Central Bank of Russia, with most of those assets in Europe. Russian central bank assets held in the US likely only amount to $4–6 billion.

Despite increased flows of foreign assistance, it is uncertain whether Ukraine has enough to cover its budget deficit this year

Although most of Ukraine’s direct foreign support for its budget shortfall and military needs dried up in the first two months of 2024, aid again started to flow in March. By mid-April, Ukraine had received $10.2 billion in budget support, of which $4.9 billion came from the EU’s 50-billion-euro Ukraine Facility. Nearly all support will be provided in the form of low-interest loans. In addition, Ukraine has raised $3.5 billion this year from its domestic bond market.

Even with revitalised foreign support, Ukraine could struggle this year in covering its budget deficit. Ukraine’s finance ministry reports that total foreign financing needs for 2024 amount to $36 billion, of which about $14 billion must come from sources other than the US aid package. Ukraine has the possibility to draw on the EU’s Ukraine Facility and the IMF’s Extended Fund Facility (EFF) by keeping in compliance with the established criteria for access to such financing.

Under the EFF, Ukraine is entitled to draw roughly $900 million quarterly. The IMF’s next scheduled assessment of economic performance to secure more financing is in June.

The EU’s Ukraine Facility, which runs from 2024 to 2027, will likely be the largest single source of funding in covering Ukraine’s budget shortfall this year. The European Commission disbursed 4.5 billion euros as bridge financing for Ukraine in March and the second tranche of 1.5 billion was scheduled at end-April. Adoption of the Ukraine plan in the EU will enable the Commission to further disburse up to 1.9 billion euros in pre-financing for Ukraine until regular disbursements would start. Criteria compliance will be reviewed every three months, and if met, will entitle Ukraine to the release of a subsequent tranches, mainly in the form of concessional loans. In 2024, two tranches of the Ukraine Facility will likely be released. The total direct budget assistance of the Ukraine Facility is about €33 billion during 2024–2027.

Even if Ukraine’s budget needs are currently expected to ease in coming years, the assurance of support funding remains shaky. For example, Ukraine’s National Bank estimates that the need for foreign financing in 2025 should decline to $25 billion and in 2026 to $12 billion. The course of the war, however, makes these estimates subject to high uncertainty.

Positive surprises in Ukraine’s 2023 growth; inflation continues to slow

In 2023, Ukraine’s GDP grew by 5.3 % y-o-y after the previous year’s drop of 28.8 %. In addition to the low basis reference, growth was boosted by the wartime production and good crop harvests. Even with the complications of war, Ukraine broke all-time per-hectare farm production volumes. Following Russia’s decision to pull out of the Black Sea grain agreement negotiated also with Turkey and the UN, Ukraine nevertheless continued to use its Black Sea shipping routes, which in turn supported fourth-quarter economic growth. Increases in agricultural output were nevertheless limited by territorial losses, mines and unexploded ordinance in farmland, as well as adverse global trends in grain prices.

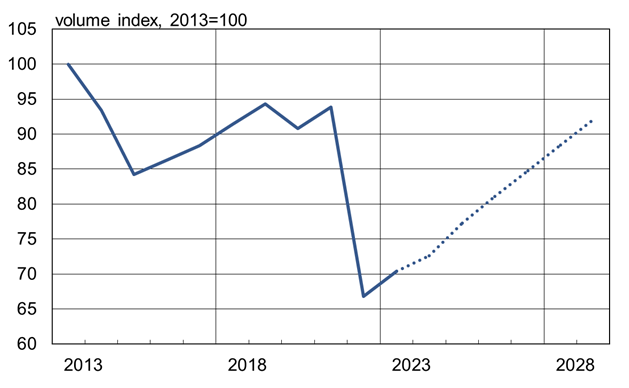

In April 2024, the IMF published its 5-year outlook for the Ukrainian economy. GDP growth should initially slow to 3.2 % this year, but accelerate in coming years. The IMF, however, expects Ukrainian GDP even in 2029 to be about 2 % lower than in 2021 before the Russian invasion and about 8 % below its 2013 level preceding Russia’s illegal annexation of Crimea. Again, ongoing war subjects this forecast to significant uncertainty.

The latest IMF estimates suggest Ukrainian GDP will still fall short of pre-invasion levels in 2029

Note: Dotted line indicates IMF projections.

Sources: IMF, BOFIT.

War has reshaped Ukraine’s GDP structure

Unsurprisingly, the biggest supply-side change has been the increased share of state administration, which grew from 7 % of GDP in 2021 to 22 % in 2023. Other core production sectors included retail and wholesale trade (share 13 %), agriculture (9 %) and manufacturing (8 %). Agriculture’s share has slightly surpassed that of manufacturing over the past two years. Most of this change reflects the demise of Ukraine’s once-mighty steel industry. 2023 steel production was only about a third of pre-invasion levels due to loss of two of the country’s main steel mills to Russian occupation and important export routes. The huge increase in defence production last year partly offset Ukraine’s loss of export demand. The evolving structure of Ukraine’s economy over the past two years is discussed in greater detail in a recent BOFIT Policy Brief.

The war has also come with demand-side implications. Public sector consumption increased from 19 % of GDP in 2021 to 41 % in 2023. In the same period, the share of household consumption fell by 12 percentage points to 63 % of GDP. The share of fixed investment was up by 3 percentage points from 2021 to the equivalent of 17 % of 2023 GDP.

Ukraine’s slowing growth in consumer prices has continued this year. In March 2024, 12-month consumer price inflation slowed to 3.2 %, far below its peak of almost 27 % in October 2022. While the biggest factor in the March slowdown in inflation was the drop in unprocessed food prices (down 4.9 % y-o-y), Ukraine’s central bank has assessed that the food price drop was likely transitory. Food prices have faced downward pressure due to bumper harvests and increased domestic supply caused by restrictions on food exports to EU countries due to border protests. The slowdown in energy price growth and stability of the hryvnia’s exchange rate also contributed to dampening inflation.