BOFIT Forecast for China 2025–2027

2/2025, published 10 November 2025

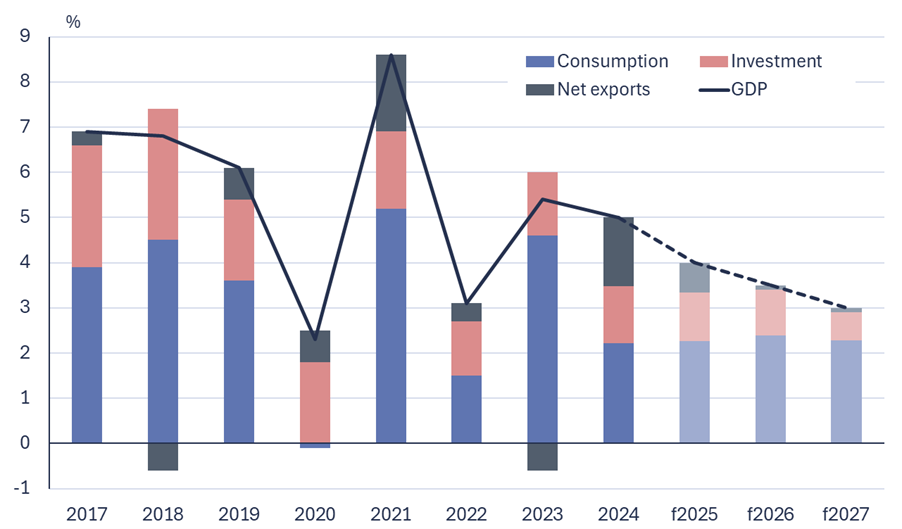

Lifted by strong exports, China’s economy has grown slightly faster this year than our previous forecast anticipated. GDP growth has been slowing in recent months, however, and we expect the slowdown to continue throughout the 2025–2027 forecast period, and reaching a rate of around 3 % p.a. in 2027. The support from exports for economic growth will weaken, fixed investment growth will slow, and domestic consumption growth will be insufficient to maintain the current pace as the population ages and shrinks. There is no evidence that the government is forging ahead on the major structural reforms needed to accelerate growth. Given the large uncertainty surrounding China’s statistical data, we expect the gap between China’s reported and actual GDP growth rate to persist in coming years.

Chinese economic growth this year has outstripped the pace we predicted in our previous forecast last April. Despite increased trade barriers, export growth remained robust, which in turn supported economic growth clearly more than expected. Boosted by strong exports, China’s National Bureau of Statistics (NBS) reports that real GDP growth in January-September was 5.2 % y-o-y. However, uncertainties remain about the reliability of official statistics due to the political importance of hitting the official GDP growth target. Indeed, BOFIT’s alternative calculation of the Chinese GDP growth rate suggests that growth this year has been roughly one percentage point below the official estimate, which is in line with the alternative GDP estimates of other sources.

While it is a near certainty that the NBS will report 2025 GDP growth in line with the government’s official “about 5 %” growth target, we expect the actual pace of GDP growth to undershoot official figures, coming in at around 4 % this year, around 3.5 % in 2026 and 3 % in 2027. We expect the pace of GDP growth derived from alternative calculations and China’s official figure to remain far apart as China’s decision-makers continue to set unreasonably high economic growth targets.

GDP growth is restrained by multiple structural factors, including China’s ever-shrinking and rapidly ageing population. China’s growth paradigm, which emphasizes hefty capital investment, faces a problem of diminishing returns as huge amounts of capital have already been sunk in unprofitable or barely profitable ventures. Progress in needed structural reforms has been slow, and overall productivity gains have been feeble. While Chinese economic growth is not as high as earlier, the pace of growth remains relatively brisk compared to advanced economies or the global economy. The disparities in branch-specific growth are expected to remain large in coming years. Rapid growth is expected in industries deemed strategically important by the government, as well as in branches that support such industries.

Export-driven growth fades

Robust exports have boosted Chinese economic growth since late last year, providing support to GDP growth that has been exceptional even by China’s own historical standards. The surge in Chinese exports has been driven in part by United States tariff policies that motivated US importers to build up inventories of Chinese products ahead of the threatened imposition of higher tariffs. With exports to the US beginning to decline sharply, Chinese exporters have found new markets elsewhere, and Chinese producers seem to have also found routes via third countries to circumvent potentially high US import tariffs. Due to strong goods exports and weak imports, China’s current account surpluses have reached extraordinarily high levels.

A more general factor driving China’s strong export performance has been the excellent price competitiveness of Chinese goods in global markets. The July reading of the US import price index for Chinese goods, for example, reached its lowest level in its over two decades of existence, before rebounding slightly in August. Producer prices in China have declined considerably in recent years, due, for example, to significant production capacity increases in industries fuelled by government subsidies. At the same time, domestic demand growth has remained flat. Moreover, prices have risen in China’s main export markets in advanced economies. On top of diverging inflation trends, the yuan’s exchange rate has weakened against many currencies, and the euro in particular. The yuan’s real effective (trade-weighted) exchange rate (REER), a measure of export price competitiveness, is at its lowest level in over ten years.

The volume of China’s goods exports has shown signs of a slight growth slowdown in in recent months. We expect export growth in the years ahead to fall below the current pace as Chinese products confront higher trade barriers around the world. Not only has the use of additional tariffs, surcharges and outright bans increased, the US has become more aggressive in curbing imports of Chinese origin entering the US via third countries. Even developing countries have erected new trade barriers. For example, Russia’s increased recycling fees on imported cars have halved Russian imports of Chinese car this year, and Russia’s fees were just recently increased further. Brazil last summer also decided to raise tariffs on electrical vehicle (EV) imports to stem the flood of Chinese EVs onto its domestic market. China’s own responses such as restricting exports of rare earth metals, support to Russia and weakening conditions for foreign firms operating in China have done little to build trust. It is also difficult to see China further enlarging its share of global goods exports to a significant extent. Import volume growth, however, has picked up recently, so we expect imports to continue to rise throughout the forecast period. With slowing export growth and rising import growth, we should see the current account surplus shrink somewhat. Even so, China’s massive current account surpluses will continue to exert appreciation pressure on the yuan’s exchange rate.

Steady growth in consumer demand as fixed investment growth slows

Domestic consumer demand is now the main driver of economic growth in China. Despite weak consumer confidence in the economy, the ongoing slide in housing prices at the national level and a tough labour market, over half of GDP growth this year should come from increased domestic consumption. In recent months, consumer confidence appears to have recovered slightly, and the steepest drops in real estate prices seem to be in the past. The government’s decision this summer to introduce a national child benefit and free preschool should bolster household confidence and slightly increase the opportunities for households to consume. On the other hand, the incentive programme launched last year to encourage people to replace old home appliances and electronics is rapidly losing steam, while the consumer credit subsidy programme announced last summer seems to have had little impact. Due to a lack of statistical data, it is also impossible to assess labour market conditions. To deal with soaring youth unemployment, the government is offering direct subsidies to companies that employ young people and ordering state-owned enterprises to hire more young people. The efficacy of the measures so far appears limited.

The sharp contraction in real estate construction remains a drag on investment growth. Nominal real estate investment and new building starts (measured in floorspace) have both contracted by roughly 20 % y-o-y this year. Apartment sales continue to slide, albeit at a rate not as steep as earlier. As newly constructed apartments come on the market, the volume of vacant apartments (measured in floorspace) on the market awaiting sale continues to rise, even as China’s population decline is undercutting housing demand. While the national situation appears grim, the real estate market is characterised by large variations across cities. Thus, we expect the decline in real estate construction to end at some point during the forecast period, but do not see real estate construction activity supporting economic growth to any significant extent.

Investment unrelated to real estate continues to grow, especially in the automobile and other vehicle industries. Even so, fixed investment growth overall appears to have slowed significantly in recent months. Intense competition, falling prices and the weak domestic economy have forced an ever-widening circle of industrial firms into the red – and despite government policies that increasingly favour domestic firms in public procurement. Declines in industrial capacity utilisation also reduce the incentives for new capital investment. During the summer, president Xi Jinping emphasised the government’s need to deal with excessive price competition between firms. However, there is still no indication that there will be any significant changes to industrial subsidies that encourage investment. The ratio of fixed investment to GDP remains astronomically high at 40 %, even if its share of GDP has declined gradually in recent years. We expect this trend to continue in the years ahead, even with high investment growth in certain sectors. For example, the grid for charging electrical vehicles will be greatly expanded in coming years, along with renewable energy production capacity.

With fiscal stimulus options limited, attention shifts accommodative monetary policies

China has long run huge public sector deficits. The IMF puts general government deficit at over 10 % of GDP, implying that public-sector indebtedness has risen rapidly. Most debt has been accrued by local governments burdened for years with the responsibility of shouldering the costs of economic stimulus and dealing with the Covid-19 pandemic. At the same time, the collapse of the real estate sector has reduced once-gushing income flows to local governments from the sale of land use rights to mere trickles. Assessing the situation of local governments and public finances as a whole is complicated by the fact that many public functions take place off-budget. China’s launch last year of a multi-year programme to shift hidden debt onto the books of local governments is therefore most welcome, and hopefully will increase transparency with regards to local government finances. Possible fiscal stimulus measures will depend, in particular, on the central government, which enjoys more room to manoeuvre. Over the longer run, public-sector expenditure and revenue must be balanced to reduce the deficit and slow the rate of indebtedness. Given the significant spending pressure facing the government, this will be a daunting challenge. The healthcare costs for China’s rapidly ageing population and public spending on pensions are already climbing briskly.

Price trends remain subdued with consumer price inflation running close to zero and producer prices declining. Moreover, the interest-rate gap with Western countries has narrowed as policy rates have fallen in other countries and depreciation pressure on the yuan seems to have eased. The People’s Bank of China has nevertheless been quite cautious this year about moving to a more accommodative stance. At the moment, it appears that the central bank is in a position to relax the monetary stance to boost inflation and support the economy, even if such a move would put pressure on the exchange rate.

Positive economic policy steps include the above-mentioned national child benefit and free preschool. These are steps in the right direction in bolstering household finances and reducing the need to save. The gradual increase of retirement ages, which began in January 2025, should improve China’s economic prospects. Moreover, the increase in retirement ages remains gradual enough to assure only modest impact on annual economic growth. China’s decision-makers have paid considerable lip-service to removing regional trade barriers, but progress to date seems to be modest. Despite these positive steps, the Communist Party of China confirmed at the end of October that the country will continue to pursue the similar economic policy priorities in the new five-year plan as it has in recent years. Efforts will continue to target industrial development and strengthen technological and scientific self-sufficiency. The plan includes the familiar trope calling for increasing the role of domestic consumer demand in the economy, even if the likelihood of reforms that could actually transform the structure of the Chinese economy to make it more consumption-driven remains remote.

Forecast uncertainties

Uncertainty in the global economy has increased in recent years. US-China relations will remain frayed, with competition between the two superpowers intensifying. While it is impossible to predict how these tensions ultimately manifest themselves, it is certain that they will have significant impacts on the Chinese economy. Chinese support for Russia’s war of aggression on Ukraine and the tightening of export controls with regard to rare earth metals keep China’s relations with Europe and other advanced economies tense. The risk of further escalation of the situation in Taiwan during the forecast period could also have major impacts on the Chinese economy.

The actual condition of China’s financial sector is something of a black box. The slowing of economic growth to a pace below Chinese expectations, the Covid-19 pandemic, the collapse of the real estate sector and the continued rise of loss-making firms must eventually be reflected on bank balance sheets. At the very least, bank funds are tied up in unprofitable businesses and thus unavailable to fund profitable projects. Indeed, the growth pace of bank loan stocks has fallen by nearly half over the past two years. China’s financial sector has become an increasingly complex entity, making official oversight ever more challenging. Thus, there may be major hidden risks lurking in the sector nobody has anticipated.

Chinese officials have steadily tightened surveillance and restrictions on civil liberties since Xi came to power. The atmosphere surrounding discussion of economic issues has also become quite stifled. Not only has it become more difficult to talk about financial imbalances, the uncertainty surrounding statistical data has increased. In certain respects, China’s economy seems to be shrouded by an increasingly thick veil of fog. Worryingly, this complicates the work of Chinese officials preparing economic policy and increases the risk of serious of policy mistakes.

Figure 1. China’s GDP growth, factors contributing to growth and BOFIT forecast for 2025–2027

Sources: China National Bureau of Statistics, CEIC and BOFIT.