BOFIT Weekly Review 32/2025

China introduces nationwide childcare subsidy and free pre-school education

China’s State Council announced last week the introduction of a childcare benefit of 3,600 yuan (430 euros) a year. The tax-exempt allowance will be paid out to families once a year for every child with Chinese citizenship under three, regardless of the child’s domicile. This year’s child benefit will be paid retroactively to all families with children meeting the criteria as of January 1, 2025. This includes all children born before 2025, as long as they have not yet turned 3 by January 1, 2025. China’s finance ministry reports that 90 billion yuan (10.8 billion euros) has been preliminarily budgeted for this purpose. About 28 million children were born in China over the past three years. The government expects to dole out roughly 100 billion yuan (about 0.07 % of GDP) a year in universal child subsidies.

While some local governments in recent years provided modest social benefits for childcare, the national childcare subsidy is the first of its kind. China had never implemented universal social support in the form of financial assistance. The benefit is also exceptionally broad as the government’s announcement does not limit the benefit to children born within wedlock or based on family means. Earlier, only the poor in China typically qualified for general income and healthcare supports. The new subsidy is naturally most welcome for low- and medium-income families. Average per capita disposable income in China last year was around 41,300 yuan, but low-income persons averaged just 9,500 yuan a year and middle-income persons just 34,000 yuan. Thus, the additional 3,600 child subsidy for a family with two parents and one young child would see an income boost of nearly 19 % for a low-income household and about 5 % for a middle-income household.

China’s State Council also announced on Tuesday that it would gradually phase in free pre-school education. Starting with the autumn school term this year, every child during the year before they enter primary school would be entitled to attend a state-funded daycare free of charge. For children attending private daycare, the cost would be reduced in an amount proportional to the amount otherwise paid for a child in a public preschool programme. The programme covers the cost of daycare and education, excluding meals.

The average cost to a family for keeping one child in daycare is 8,220 yuan a year. At the end of last year, about 36 million children were enrolled in daycare. Children in China typically go to daycare between the ages of three and five and start elementary school at the age of six. Thus, from the start of autumn, daycare services will become free for over 10 million children. The central government and local governments will split the costs of the programme based on the financial conditions of the respective local government, with wealthier ones such as Beijing and Shanghai going 50-50 on the bill.

In China, starting a family is increasingly rare

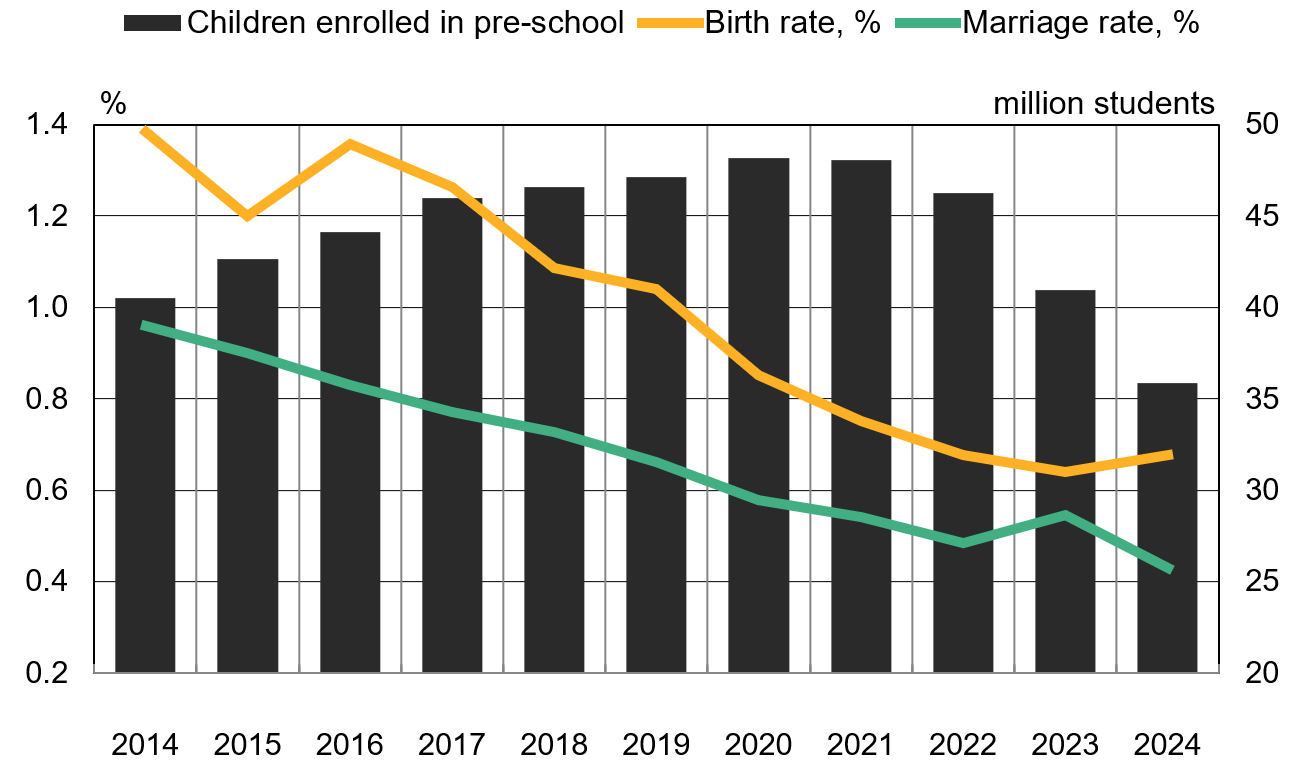

Note: Marriage rate is new marriages divided by population that year. Sources: BOFIT, China National Bureau of Statistics and Ministry of Education.

China’s population has been shrinking over the past three years. In 2021, China abolished all remaining restrictions on family size due to its rapidly ageing population and low birth rate. China’s birth rate fell between 2016 and 2023, but then rose slightly last year thanks to government incentives and the general perception that it was good luck for a child to be born in the Year of the Dragon, the fifth year in the Chinese 12-year zodiac. China’s low birth rate reflects a drop in the number of couples seeking to have children and falling fertility rates. A record low of 6.1 million marriages were registered in China last year. Children are typically born in wedlock in China. The measures now published are a significant development for China, which traditionally has had a quite meagre social safety net. The central government hopes the programme will deter new families from delaying or refraining from having children due to financial reasons, though it is unlikely to do much to stimulate China’s weak domestic demand.