BOFIT Weekly Review 45/2023

Hundreds of foreign firms continue to do business in Russia despite huge risks

With Russia’s all-out war of aggression on Ukraine in February 2022 and the wide-ranging economic sanctions it triggered, many foreign companies announced plans to exit the Russian market altogether. Estimates of the number of firms that have actually exited the Russian market vary, but it is also evident that hundreds of foreign corporations continue to do business in Russia despite the war.

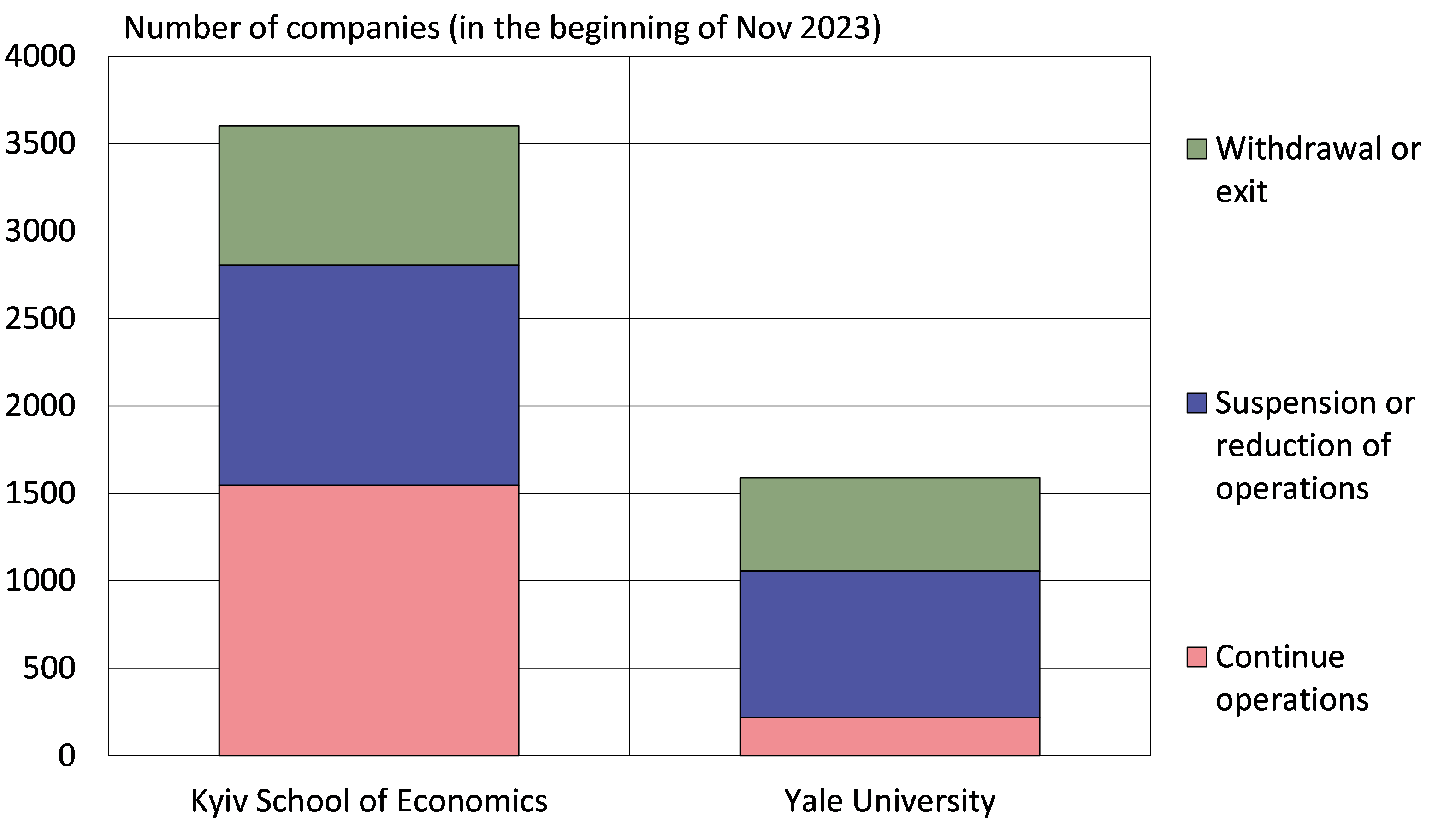

The Leave Russia database maintained by the Kyiv School of Economics (KSE) shows that about 20 % of foreign firms have withdrawn all business in Russia or exited the market. The database currently tracks about 3,600 firms. The Yale CELI List of Companies Leaving and Staying in Russia tracks roughly 1,600 firms and estimates that about third of these firms has withdrawn or exited Russia. The methods and sources used in the databases differ somewhat in their methods of evaluating company operations.

The share of companies that have left Russian markets varies much across countries. The KSE database shows that about half of firms from countries that imposed sanctions on Russia are either in the process of leaving or have already withdrawn from the Russian market. In relative terms, Finnish and other Nordic companies have been most active in leaving the Russian market. Within EU, the share of companies still present in Russia is highest (about 80 %) among companies based in Greece, Italy and Austria. Only a tiny percentage of Chinese, Turkish and Indian firms have announced any plans to exit Russia.

Hundreds of foreign firms have chosen to keep doing business in Russia

Sources: Kyiv School of Economics, Yale University, BOFIT.

Underlying economic and administrative factors

Despite the war, some foreign firms are tempted by the juicy profit potential of remaining in the Russian market. Many competitors have left and import competition has also reduced. According to a report by the KSE, corporations that chose to continue to operate in the Russian market collectively earned profits from Russia of about 14 billion dollars last year. At the same time, they supported Russia’s budget revenue by paying 3.5 billion dollars in profit taxes alone. Some firms have argued that they need to stay in Russia for humanitarian reasons because they produce or sell necessities such as medicines and food.

Some companies exiting Russia have experienced huge losses from having to dispose of assets at fire-sale prices or write down Russian assets as complete losses. The Financial Times estimates that firms on its list of Europe’s top 600 companies have collectively suffered losses of roughly 100 billion dollars in withdrawing from the Russian market. The largest losses have been borne by international energy giants such as BP and Shell. The pain of such losses last year was offset to some extent, however, by robust profits these companies enjoyed on the spike in oil & gas prices following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.

Russia has made exiting from the market very difficult since the invasion of Ukraine. For example, a firm from a “non-friendly” country (country imposing sanctions on Russia) that seeks to sell its business in Russia must first get official permission. The process of getting such permission can take several months. Officials also expect the sale to be realised at substantial discounts with some of the money from the sale surrendered to Russian officials. Russian media reports that such surcharges to date have raised 80 billion rubles (about 1 billion dollars) for state coffers. Under Russia’s 2024 budget framework, however, this temporary revenue stream is expected to dry up next year.

Russian market risks large, growth outlook weak

The risks associated with operating in the Russian market have increased tremendously since the start of the war. The overall attitude towards foreign companies is hostile and their operations have been complicated by administrative measures. Limits on capital movements make it very difficult for corporations to move money abroad. These problems are not limited to companies from “unfriendly” countries. For example, Indian oil companies are currently struggling to repatriate roughly 600 million dollars in Russian dividends.

According to a recent report by a Russian law office, cases brought against foreign firms in Russia have increased substantially since the war started. Ever more often in these cases assets of foreign companies become subject already to pre-judgment seizure of assets or arrests. The report notes that such measures against foreign firms are likely to increase.

Changes in Russian law this year now permit freezing or seizure of the assets of foreign firms by Russian officials. Russian officials have already this year confiscated the Russian operations of Finnish energy company Fortum, Danish beverage-maker Carlsberg and French food giant Danone. In addition, Russian officials can commandeer any firm operating in Russia to participate in the war effort.

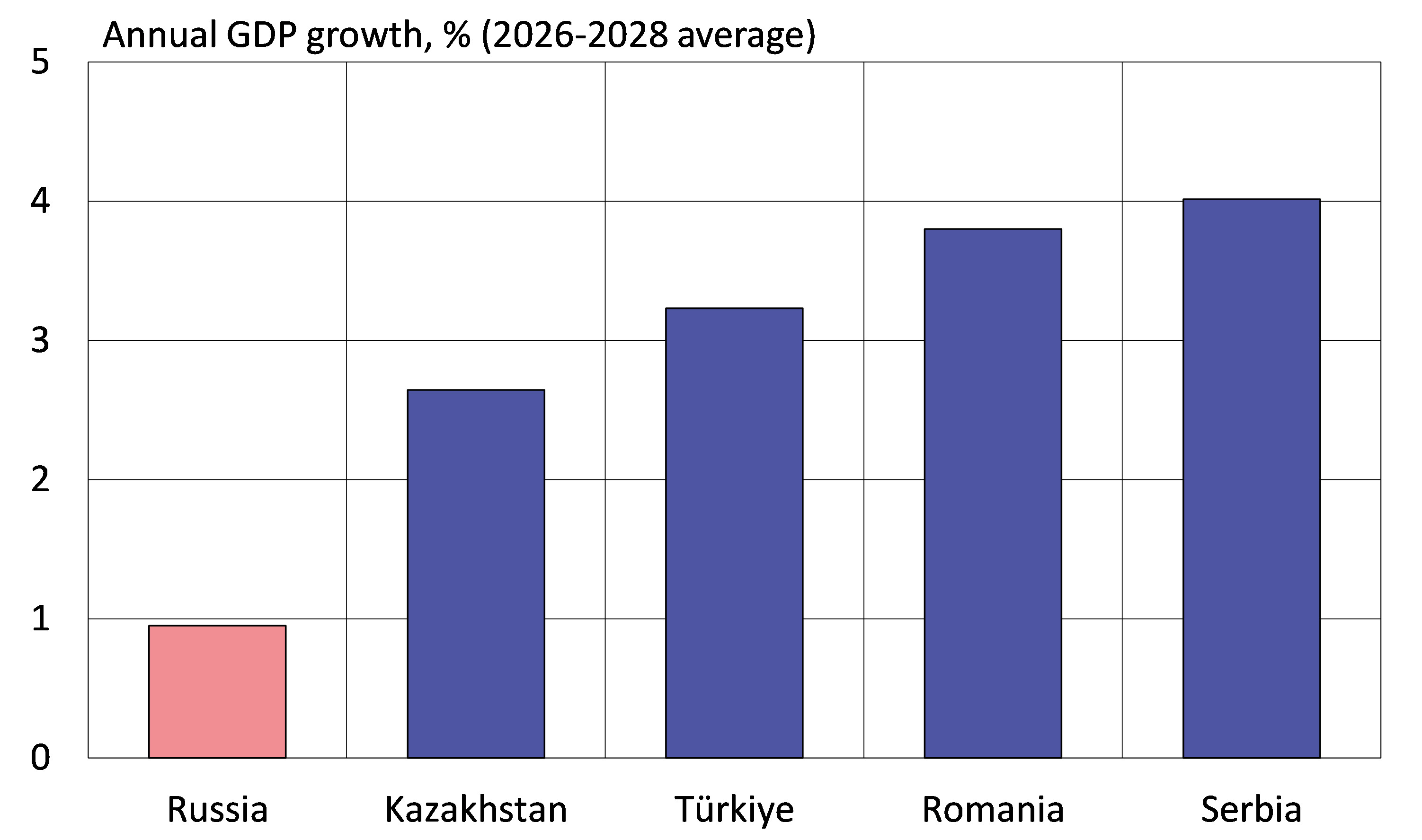

Despite huge risks, especially the longer-term growth outlook for the Russian economy is quite feeble. According to the IMF’s latest WEO, Russia is among the most slowly growing economies in coming years together with countries like Equatorial Guinea and Belarus. Russian GDP growth is predicted to be significantly lower compared to most other countries with a similar income level.

The IMF expects Russian GDP to grow considerably more slowly in 2026–2028 than GDP of other countries with similar income level

Sources: IMF WEO October 2023, BOFIT.

Most Finnish firms no longer do business in Russia

The business relations of Finnish firms with their Russian counterparts have collapsed since the invasion of Ukraine. Finnish firms have left the Russian market entirely with but a few exceptions. According to a just-released survey of Finnish export firms by Finland’s Chamber of Commerce, only 2 % of respondents said that their company still had operations in Russia, down from a pre-invasion level of 80 %. A few firms reported that their withdrawals from Russia were still ongoing.

A VATT Institute for Economic Research study finds that the impacts from the loss of exports to Russia on Finnish firms have generally been quite limited. Although exports of firms exporting to Russia contracted more severely than those of other export firms in spring 2022, affected firms made the transition with little change their levels of overall sales or number of personnel compared to pre-invasion levels. The authors argue that the small impact reflects the waning importance of Russia as an export market and the ability of affected firms to identify alternative export markets.