BOFIT Weekly Review 49/2025

New sanctions reduce export price of Russian oil

In late October, the United States placed Russia’s two largest oil producers, state-owned Rosneft and privately-held Lukoil, on its revised sanctions list. The combined output of Rosneft and Lukoil represents about half of Russian oil production. Placement on the sanctions list implies that any entity engaging in business transactions with Rosneft, Lukoil or their subsidiaries could be considered criminal violations by US authorities. With a few exceptions, the ban on doing business with these companies went into effect on November 21, following a 30-day transition period. On Thursday (Dec. 4), the US treasury department granted Lukoil extensions to negotiate the sale of its gas stations outside Russia. Otherwise, companies or persons continuing to do business with these companies could expose themselves to secondary sanctions measures.

The GazpromNeft and Surgutneftegaz oil companies were placed on the US sanctions list already in January. Surgutneftegaz was also added to the EU sanctions list in May. Presently, over 70 % of Russia’s total oil production comes from oil fields operated by sanctions-listed companies. Russia’s four largest oil producers also account for the lion’s share of oil and petroleum product exports. The purpose of sanctions is to pressure refineries that do business with listed firms to cease purchases of Russian raw material inputs. Interest is now focused on the reactions of major Indian and Chinese buyers.

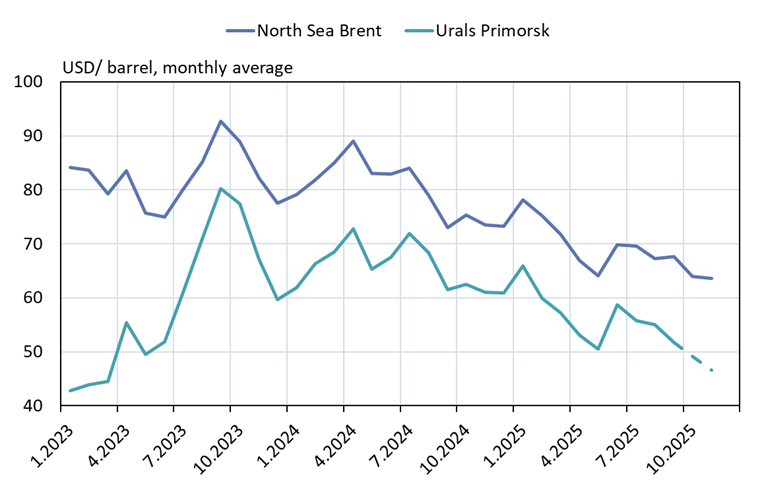

While the responses of major buyers are still somewhat murky, the market price of Russian crude has clearly declined in recent weeks. Media reports suggest that the price of Urals, Russia’s main export blend, has fallen well below $50 a barrel as sellers scramble to find buyers. At the same time, the difference between the average prices of Russian Urals and benchmark North Sea Brent crude has widened to nearly $20 per barrel. Before the full-on invasion of Ukraine, the Urals-Brent price difference was typically $1–2. In 2023, the Urals price averaged $23 less than the Brent price. The difference had settled around $14 over the past two years. The large price gap between Urals and Brent blends is indicative of the costs to the Russian economy caused by sanctions.

Analysts report that Russia’s oil export volume has only contracted slightly, but amount of oil at sea in tankers awaiting buyers has increased substantially. Moreover, Russian oil for export is increasingly loaded into ships without designation of the cargo’s destination or final buyer. The market situation could take months to settle.

While the price of benchmark Brent crude is down, the price of Urals crude has declined even more

Sources: IEA, CEIC, BOFIT.

Sanctions lists now cover most of Russia’s shadow fleet vessels

With the tightening of sanctions on Russian oil exports, Russian oil exporters have shifted to using vessels not covered by Western insurance services (including members of the International Group of P&I Clubs). Vessels involved in transport of Russian oil with third-country ownership and insurance coverage are often referred to as Russia’s “shadow fleet”. While many “shadow fleet” vessels are in reasonably good condition and professionally maintained, the fleet also includes antiquated vessels in poor condition with questionable seaworthiness.

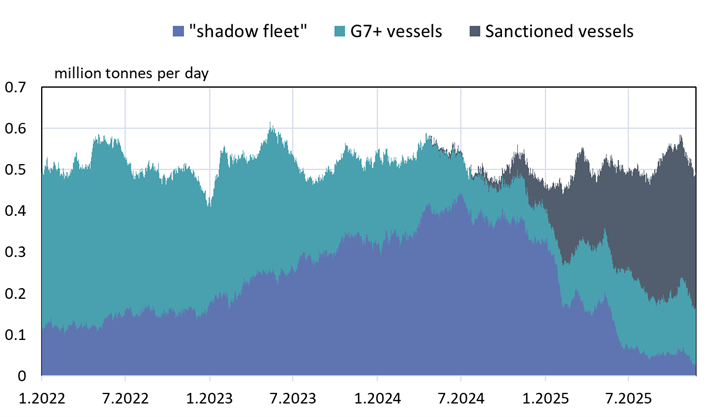

The EU, UK and US over the past year have focused intensively on sanctioning shadow fleet vessels in the worst shape and vessels obviously involved in circumventing sanctions. Listed vessels are banned from EU ports and may not be offered insurance, forwarding or financial services. With the announcement of the EU’s 19th sanctions package, 557 listed vessels are now subject to sanctions, with the result that it is quite difficult for these sanctioned vessels to operate outside the oil trading sphere of Russia, Iran and Venezuela. For this reason, the number of sanctioned vessels hauling Russian oil has soared. Over half the ships carrying Russian export crude are on sanctions lists. In November, sanctions-listed vessels accounted for over 60 % of Russian crude transported by sea, while the share of tankers from G7+ countries accounted for just under 30 %. The share of G7+ vessels involved in the export of petroleum products is clearly larger.

The evasion of sanctions and efforts by shipowners to keep their vessels off sanctions lists has led to the use of rust-bucket vessels of scrapping age, forgery of insurance certificates, as well as provision of false flag certificates from shady operators. CREA’s recent “Flags of Inconvenience” report asserts that 13 % of Russian oil transported during the first nine months of this year were shipped on vessels flying false flags. Under international maritime law, every ship must have a flag state (legal home) that conducts regular inspections to assure such things as vessel seaworthiness and compliance with safety and environmental rules.

The share of sanctions-listed vessels hauling Russian crude has soared this year

Source: CREA.

Russian export routes remain unchanged even with sanctions

The production and export volumes of Russian crude oil have remained roughly at the same level for several years. Russia exports an average of about 5 million barrels of crude oil a day along with roughly 2.5 million barrels of refined oil products. While three-quarters of Russian crude oil is exported via sea, most pipeline oil is transmitted to the Chinese market via the Eastern Siberia-Pacific Ocean (ESPO) pipeline. Petroleum products are almost entirely exported by sea. Because exports to the EU have largely dried up, the largest buyers of Russian oil exports currently are oil refineries in China and India. This is unlikely to change, even if exports to India and China decline in the coming months due to the latest sanctions.

Data compiled by the Centre for Research on Energy and Clean Air (CREA) show that nearly half of Russia’s total oil exports ship via Baltic Sea ports, specifically the ports of Primorsk and Ust-Luga. Another quarter of Russian crude ships via ports located on the Black Sea, with the remaining share (just over 20 %) shipped in the Far East. Thus, the Baltic Sea is Russia’s most important route for shipping crude oil and petroleum products to international customers – and it is unlikely that this arrangement would change any time soon. Construction of port infrastructure and pipelines to support new shipping and transmission routes take years, if not decades. The shallow, rocky Gulf of Finland is particularly tricky to navigate. This has amplified concerns about the condition and structural adequacy (e.g. ice class requirements) of shadow fleet vessels, crew seamanship levels and the critical winter navigation skills required to operate in the Baltic.

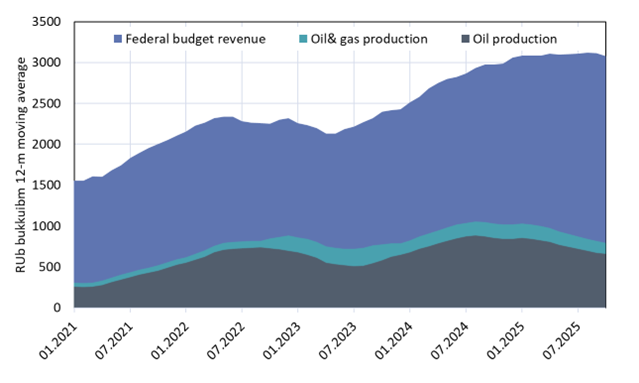

Falling oil prices shrink contribution of oil income to federal budget revenues

Oil export volumes no longer directly affect Russia’s public sector revenues. Following the abolition of the export tax, oil producers now pay an extraction tax based on total production volumes. The oil extraction tax has accounted for 25–30 % of federal budget revenues in recent years. The size of the extraction tax depends on the average export price of Russian crude oil. With the decline in oil prices, this year’s tax take is expected to fall well short of the budget target. In the first ten months of this year, revenues from the production tax were down by 25 % y-o-y. The initial budget assumed an average export price of $70 per barrel, but the actual average price was likely around $60 a barrel. Export prices fell considerably in November, adding to Russia’s budgetary pressures. further increasing budgetary pressures.

Oil income represents a decreasing share of Russia’s federal budget revenues

Sources: Russian Ministry of Finance, CEIC, BOFIT.