BOFIT Viikkokatsaus / BOFIT Weekly Review 2022/48

Last weekend saw a wave of protests around China triggered by an apartment building fire in the city of Ürümqi, capital of the western province of Xinjiang. Ten people died in the fire due to covid lockdown restrictions that complicated rescue efforts. Protests are hardly unusual in China, but they are typically localised and involve a narrow issue such as unpaid wages at a particular manufacturing facility. Such demonstrations are insignificant relative to China’s massive population.

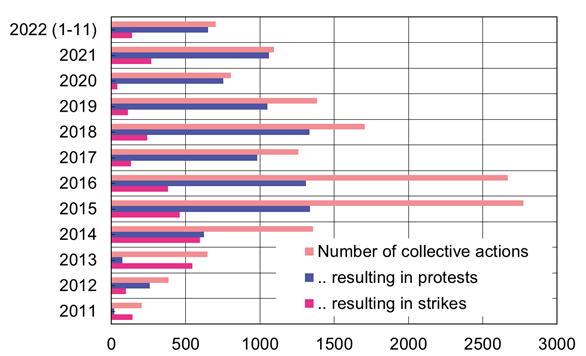

The Hong Kong-based non-governmental organisation China Labour Bulletin (CLB) has tracked collective labour actions in China since 2011. As of November this year, they had registered nearly 15,000 labour actions over the past 12 years, including nearly 9,500 protests and over 3,100 strikes. According to the CLB, about 80 % of Chinese protests recorded since 2011 involved fewer than 100 people, and only five protests had attracted at least 10,000 people. The last big demonstration in 2018 involved teachers in the city of Harbin in northeastern China demanding better pensions. Most of the 701 labour protests recorded this year had involved fewer than 100 people. Only 128 protests with over 100 people had been recorded this year until November and none involved over 1,000 protesters.

The wave of demonstrations last weekend was atypical in many ways. According to media reports, they drew thousands of people to the streets in at least ten cities, including Beijing, Shanghai and Guangzhou. The Financial Times estimates that the number of participants likely numbered in the tens of thousands. Students also arranged on-campus protests, including at the prestigious Tsinghua University in Beijing. Motivations for protests include dissatisfaction with zero-covid policies, but also unhappiness with China’s leadership generally, the stifling of free speech and excessive censorship. The protests have been dubbed the “A4 Revolution” or “White Paper Protests” as protesters in city streets and on university campuses have shown their outrage by holding up blank sheets of A4-size paper.

Public gatherings were obstructed early this week with police presence ramped up in many cities. However, on late Tuesday (Nov. 29) evening, protests in Guangzhou turned violent. According to media reports, participants in last weekend’s protests in many cities have been tracked down by the police and brought in for questioning. Under the guise of worsening covid situation, university students were requested by officials to return to their home districts and study remotely online. Tsinghua University organised free busses for students to ferry them directly to Beijing airports or train stations.

China’s leadership has laid blame for the deleterious effects of lockdowns on local officials and tried to calm the population by responding to certain concerns about zero-covid polices. Over the past few days, government officials have announced that covid restrictions should not interfere with ambulance transport or rescue efforts, that the barricading of buildings to hold residents inside must cease, that vaccination rates among the elderly need to be increased and that the basic needs of people during lockdowns should be better considered.

China sees frequent protests each year related to collective labour action, but protests are typically small and concern local issues.

Sources: China Labour Bulletin and BOFIT.